I realized late last week that our team was moving too fast for me to remember all of our activities each day. Especially when reflecting on a full week of progress, it was incredibly difficult to pinpoint what we had been doing on Monday. This week, I started keeping a daily log of meetings, workshops, team discussions, and prototyping progress. Looking back upon Monday, I am stunned by how much we’ve learned this week. Even though one week will always be just 10,080 minutes, it feels like Team Petri-FI was able to stretch this week to its maximum.

We walked through the OEDK doors on Monday with many question marks. We still had not completed the breadboard circuit for our incubator, so we had yet to test the code or the heating pads. So far, we had formed a stronghold of bright ideas, but we hadn’t the time to apply them to our project. We were nearly satisfied with our heat transfer spreadsheet, which could now help us to estimate how small of a battery we may be able to use. However, we were still itching to bring our ideas to the physical realm and begin to test our theories against reality. Monday’s engineering design workshop was about low-fidelity prototyping. The principle behind creating prototypes out of the cheapest materials possible is that it helps teams to develop a tactile feel for their product. It can also aid communication within a team about physical specifications that would otherwise only be visible on a piece of paper or a laptop screen. Our team made a few prototypes out of construction paper, pipe cleaners, and aluminum foil, which helped us to learn about the overall form of our incubator designs and the connections that would need to be present in the final design. Also, after having worked mostly with the previous Minicubator and Moonrat prototypes, this was an excuse to make some designs of our own.

Troubleshooting

I have made another realization this week. Sometimes, progress doesn’t look like a new “thing” or a problem solved, or an item checked off of a list. Sometimes, progress exists only in your head. When approaching the problem of electronics, I had a mental hill to climb. On Tuesday, we spent some time with a faculty member, who walked through the previous team’s entire circuit and answered our electronics questions wonderfully. I came out of that conference room with an entirely new understanding of circuits, breadboards, and Arduinos. Before, I had seen our messy breadboard and thought to myself, “I never, ever, want to touch that thing.” However, I quickly found myself fascinated by all of the branching connections. There was a simplicity, or a new frame of mind, that I had just unlocked, as though my brain had received a firmware update.

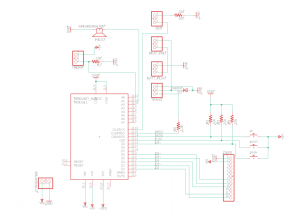

I spent much of the week applying my new knowledge of breadboarding and circuits. After the initial build of the breadboard, we noticed a few obvious mistakes, and many more that were much less clear. On a similar front, I worked hard to read through the previous team’s code in order to better understand how the Arduino interacted with the overall circuit. I added dozens of comments within the code to function as a bread trail for our team, so that all of us would eventually be able to understand the programming behind our device. Even as we made steady progress through team discussions and delegated work, much of our effort was spent on mental progress, the kind that doesn’t show itself as a physical prototype or symbol of advancement. However, we made an exciting leap on Friday afternoon.

Zero to Sixty

On Friday, we had our mid-summer presentation, in which we detailed our team’s progress in the engineering design process. It was wonderful to see the progress of the other internship teams as well, especially after only three weeks had passed. Our team had to shift focus as we prepared to share our discoveries with everyone else. When the show was done, we had a fresh perspective on the overall project goals, and we apparently had a great dose of inspiration after lunch.

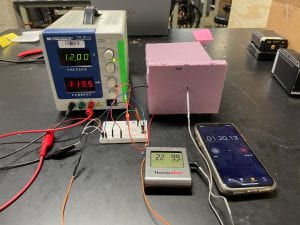

We knew the importance of testing our heating chamber prototype idea as a proof-of-concept for an incubator. We already had a power supply, excessive breadboarding materials, and pink insulation foamboard; we had a vision, and we pursued it passionately. We epoxied together an insulated box, complete with a heating pad and a stand for our Petrifilms (the biological material that we would be incubating). Then, with my entirely newfound breadboarding skills, I created my first (and most adorable) circuit, equipped with an LED and a tiny little switch to turn on the heating pad inside.

We turned it on. The instant the thermometer ticked up from twenty to twenty-one degrees Celsius, our team was beaming with delight. We’d done it! We’d conquered thermodynamics to heat our little chamber! Afterwards, it took no time at all to heat to the desired thirty-five degrees, and we collected data from a few heating and cooling cycles, until we were satisfied with our findings. Then came the main attraction.

“How about we turn it on, and just don’t turn it off, to see how hot it gets?”

“Sure.”

Now, believe me, this test was very useful for us. It would give us a theoretical limit on our chamber’s heat loss at high temperature differences, as well as informing us of any potential safety concerns in the case of malfunction. So we waited, and waited. And waited some more. Fifty. I was betting it wouldn’t get over sixty degrees, because our chamber was clearly not airtight. Fifty-five. Now, it was ticking up about a degree every five to ten minutes. Fifty-nine. Sixty! In fact, our chamber was losing so much air that we could smell something not quite right from the inside. Sixty-four. Sixty-five. Now, it was going about fifteen minutes between jumps. We swore that if it made it any further, we would stop it. Sixty-six! That’s sixty-six degrees Celsius (one hundred and fifty-one degrees Fahrenheit), or about as hot as a parked car during the Houston summer. We opened the chamber tentatively, not sure what we would find.

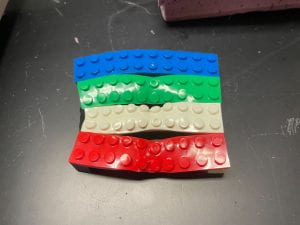

As I extracted our Lego Petrifilm stand, I immediately understood the smell coming from the inside. The heating pads, and their warm air, had melted the Legos! After extracting the heating pads themselves, I could see the crater of melted foam underneath. We understood the potential safety concerns, but we also knew that we would never expect temperatures anywhere near 60 degrees Celsius. While some teams would have been horrified by the power of their own device, we cheered for the success of our heating chamber. If melting Legos was this easy, we could surely keep a device at thirty-five degrees Celsius! Overall, Friday’s testing session concluded a long week, but we were energized by the tangible progress we had made.

-Kenton Roberts