Let me preface this post by saying I am not an emotional person. I don’t cry at graduations or weddings, and you certainly won’t catch me shedding a tear over a movie. So when I nearly broke down in the middle of a workshop on ethical innovation by Magdah (one of our TA’s), I immediately recognized two things: one, global health innovation is both extremely important and extremely easy to mess up; and two, I am on exactly the path I need to be.

When I walked through the Sallyport my freshman year at Rice, I was determined to complete a Bioengineering degree so that I could work on medical devices as a career. I had the privilege to work on a catheter prototype with Biomedical Engineering graduate students at UT Austin during high school, and my excitement from that experience inspired me to pursue Bioengineering at Rice so that I could design medical devices.

As I reflected more on my personal motivations, I began to realize that in order to feel fulfilled in my career, I would need to have a direct impact on others. Something about the look on the face of someone I’m tutoring when a concept clicks, or the determination of working alongside Nicaraguans to build a house, gives me joy in a way that nothing else can. So this presented me with a dilemma: engineers often don’t get to work directly with their users or make an obvious impact on the population. Medical devices are extremely important and lifesaving, but so often the engineers who create it aren’t able to see the impact of their work.

I then stumbled upon the Global Health Technologies program at Rice, which combined my interest in working with Nicaragua and other low Central American countries with my Bioengineering studies. Fast forward 2 years, and I’m now a Rice 360 intern. Yes, I’ve been very excited about the practical experiences I would gain here–the engineering design process, prototyping, international communication, and much more–but I didn’t truly think about the global health aspect of the internship until Magdah’s workshop.

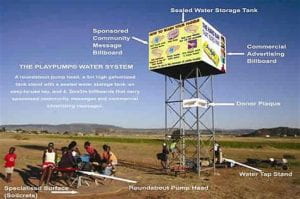

During the discussion, we focused on the example of the Roundabout PlayPump, a clever but misguided project which sought to facilitate clean water access for South African families. Although the children initially enjoyed playing on the pump, eventually they lost interest and the brunt of the pumping work fell on the mothers who, according to Dr. Taylor, described the experience as “humiliating” and “degrading.” In fact, so strong was the failure of the PlayPump that the word itself became taboo in the country.

What went wrong? The engineers working on the project were capable, intelligent, and inventive. They had no malicious intentions, but simply suffered from a case of design mismatch. As we’ve learned in our workshops, it is very important to keep the user at the forefront of the design process, since they will be the ones interacting with the technology. However, the PlayPump disregarded the desires of the actual users, the mothers who would carry the water back to their homes, and relied on children to fuel the pump instead. Since PlayPumps replaced existing pumps, these mothers were forced to use the merry-go-round themselves, which was neither dignified nor easy.

This brings me to the first lesson: although brilliant engineers can come up with a promising solution to a major problem, it is so easy for mindsets of colonialism or heroism to get in the way. Humility is vital to the design process: no one knows the need for a technology better than the population who needs it. In designing a solution without heavily and repeatedly involving this population, mistakes–such as the PlayPump–can occur.

My second lesson hit me like a ton of bricks. In feeding off of the passion of Magdah, of Dr. Taylor, of all of the interns in the room, I began to feel restless and jittery. For the first time in a while, I felt uncontainable excitement about a cause. I realized that I was exactly where I needed to be. Yes, I know, I know–that sounds like a line from the end of a Disney channel original movie, but experiencing this much passion took me back to the roots of my anticipated engineering career. Although I enjoy engineering design, my deepest motivation rests on the fact that I need to use my life to make an impact on others. And through ethical global health-centered engineering, I get to do just that.

So, to recap: the need for ethical designers is very present in our evolving world. As we grow in technological advancement, we need to avoid the temptation to place ourselves as the heroes of the story. In my future as an engineer, I hope to keep the target population involved in the design process. And, once COVID-19 is under control, I can’t wait to travel and work directly with the people of Malawi, of Tanzania, of Nicaragua, and so much more.

Thank you for making it to the end of this blog (sorry! I get verbose when I’m excited). I hope that you were able to get a clearer idea of what motivates me to be a Bioengineer, and are able to carry a bit of my enthusiasm with you 🙂

Image source: https://ppss.kr/archives/68852