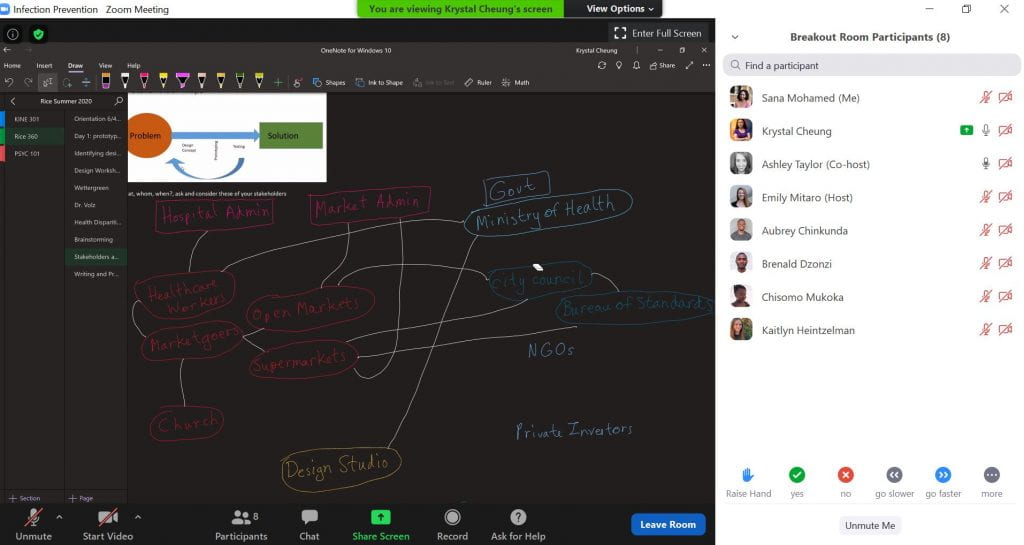

During this past week, we had the opportunity to speak to stakeholders of a wide variety of backgrounds including businessmen, nurses, non-profit heads, professors, engineers, and even other undergraduate students. Each day we presented our technologies to the various stakeholders and then were sent to breakout rooms to ask more device-specific questions and gain the stakeholders’ perspectives on our current device. This opportunity proved to be invaluable as it opened our eyes to some potential solutions to key issues we had presented and also made us aware of a few problems that we had not previously considered.

Some of the advice we collected through this experience for the walk-through decontamination unit is as follows:

- Reconsider the problem context and consider all the scenarios in which the device could be used. For example, consider the different positions that people may assume when in the unit, what they might be wearing (hats, masks, etc.), and the different types of people (children, disabled, tall, etc.). Each of these considerations will drastically impact how the device functions, and thus should be contemplated in the design of the device.

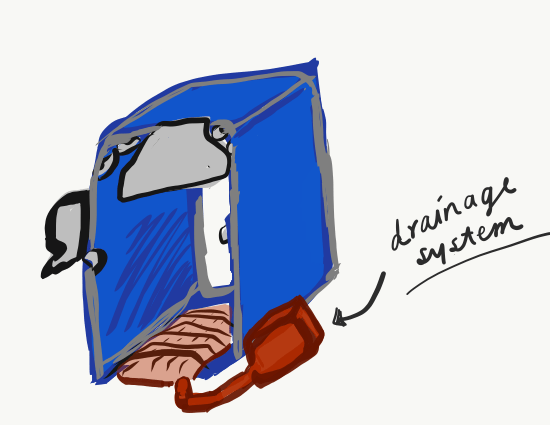

- The need to possibly readjust some aspects of our current design:

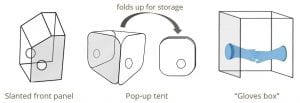

- The shape and structure of our device. Could another shape possibly result in a more positive perception of our device and be more accurate in dispensation? How could the materials of our device be altered to increase movability and decrease cost?

- The chemical that is aerosolized. Throughout this internship, a major concern of our group has been what chemical to use or how the chemical could be sprayed to limit possible negative effects on the user. To do this we will need to do further research on other disinfection methods and how to adjust the spraying area based on the user to prevent interaction of the chemicals with the mucus membranes.

- The function of the drainage system. Should the drainage system just seek to collect the runoff for disposal or should it seek to collect runoff in a manner in which it could be reused? We are currently looking into the feasibility of the latter.

- How the device is activated. In high traffic areas, there is a possible issue of false sensing of a user (false positives) that would waste the disinfectant. To prevent this we plan to look into other activation methods that would instead rely on mechanical elements, pressure plates, etc.

Some of the advice we collected through this experience for the handwashing station is

as follows:

- Reconsider the end user. How will someone unfamiliar with the device work out how to use it? What would promote them to use it? This would involve some component of education to promote proper hand hygiene procedures.

- The need to possibly readjust some aspects of our current design:

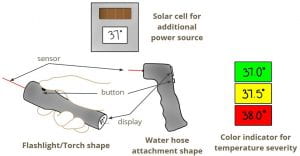

- The powering of our device. The power source of the device should be sustainable both in lifetime and in the environmental context in which it is placed. We have started to consider solar panels that would recharge the device’s battery both in outdoor and indoor settings (would work with UV and artificial light sources).

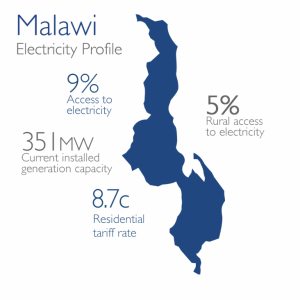

- The sanitizing agent used. Our stakeholders in Malawi noted that hand sanitizer can be very expensive so often other disinfectant agents are used. Therefore our device should be able to work with liquids of different viscosities.

- The overall structure of the device. Some of our stakeholders suggested looking into more mechanical backup options such as the use of a foot pedal. Additionally, they provided advice on how to deal with the manufacturing constraints of this setting and how they will come into play when we look to scale up.

In addition to receiving advice on our current prototypes, we also sought guidance on some possible future areas where technologies could be implemented. These areas include PPE that can be quickly disinfected and reused, quick diagnostic tests, patient room disinfection, and incubators in which procedures can be performed (instead of moving the infant to a secondary location and increasing the risk of infection).

Moving forward into the last two weeks of our internship, we hope to further research these areas that were brought up by our stakeholders and include what we find in our recommendations to the design studio. Overall, this busy week provided us with some great insights into the developmental process of our technology and into the needs of the end-users.

Rather than ending the week with our usual group workshop, some members of my team were able to meet up on Friday for a really fun activity. We played an online game that was reminiscent of charades (see image below). I had a great time and really hope that we will be able to do something like that again as it was a fun way to get to know everyone better and bond more as a team.

This past week has been a whirlwind of new ideas and I can’t wait to see where we go from here.

Signing off,

Kaitlyn Heintzelman

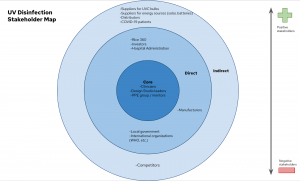

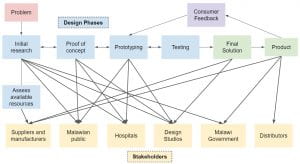

Stakeholder Map

Stakeholder Map