This past week has been the most productive yet, full of presentations, interviews, and conversations that has greatly progressed both our understanding of the project and our potential suggestions to the design studios for my team’s two prototypes. Our group workshops Monday through Wednesday consisted of interviews with our stakeholders, which are individuals, groups, or organizations that may be impacted by our project. As we previously identified with our stakeholder maps, this includes suppliers and manufacturers, the Malawian public, hospitals, design studies, the Malawi government, distributors, and more. Prior to presenting the stakeholders with our projects, we found it important to conduct further group and solo brainstorming to give the individuals we were interviewing a better idea of our direction with our project. After going through the process, my team and I selected a few designs that we wanted to present for feedback, and I drew them in a clear way to add to our presentations.

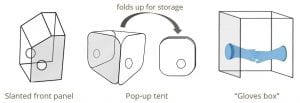

For the intubation box we focused on three design concepts. The first involved a slanted front panel to help with the ergonomics of the intubation such that the physician would not have to crouch in such an awkward position to have adequate visualization and they would rather look down into the box through the slanted front panel. The second idea is the pop-up tent which is made of a wire frame and some form of clear vinyl/plastic sheeting. This would allow the box to fold up for storage so that is could easily be stored in the hospitals in Malawi that often have limited storage closet space or excess rooms in the ORs for a large solid box. The final idea was the “gloves box”, similar to an isolation gloves box used in biology labs. This involves a thick solid ring outside the arm holes of the box where the rim of a glove would be slipped over and then the physician would insert their gloved hands into the box. This would further reduce the spread of aerosol droplets through the arm holes of the intubation box.

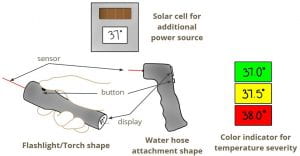

For the contactless temperature monitor we focused on two design shapes and two design features. The first shape is like a flashlight or torch (fun fact – I learned that a flashlight is called a torch in Malawi, while here in the U.S. torch typically refers to either a blow torch or a stick with a flame on one end) where the sensor receives input on the light-end of device while the display is on the opposite end. The other shape resembles a water hose attachment that has grooves to improve the ergonomics of holding the device. We wanted to avoid a gun-shaped device due to hesitation for use in today’s climate, and while our design uses similar design principles to a gun-shaped monitor, we believe the shape is different enough that it would not be misconstrued. One feature we would like to be included in the monitor is a solar cell as an additional power source so preserve the batteries. We also believe that a color indicator to indicate the severity of the temperature would be helpful for users not familiar with clinical measurements. In this design, the color green would indicate no fever, yellow would indicate a temperature that is not severe but should be watched, and red would indicate a severe fever.

With our project scope and brainstormed ideas in mind, we set out on Monday to begin interviewing our stakeholders. Our first conversations were with Edward Matengele from the MUST Innovation Center, Erin Keaney from Nonspec, Inc., Jade Kissi from the University of Michigan, and Agyen Obeng from the University of Ghana. Our main takeaways from our first day of interviews was that, first, we as a team needed to do further research on the initial background of the prototypes we received so that we could better answer a number of the stakeholder’s questions. We received important feedback for the structure of the intubation box, including suggestions for filleted edges to address safety concerns for sharp corners of the box or the idea of using heat to bend acrylic for a more rounded design. For the temperature sensor, we discussed in depth the cost of the devices components and the balance we must mind of the sensor accuracy and the cost as a more accurate sensor will be 1) more expensive and 2) less likely to be found in Malawi and will thus have greater shipping costs. We also determined from our stakeholder Erin that there is a need for a continuous temperature monitor in hospital settings that does not require human input, which is something that we will further look into as a proposal for a future project.

Our interviews on Tuesday were with Msandeni Chiume from Kamuzu Central Hospital in Malawi, Jackson Coole from Rice University, Prince Mtenthaonga from Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Malawi, Elizabeth Johansen from Spark Health Design, and Caroline Soyars from the University of Michigan Global Health Design Initiative. After feeling slightly unprepared for Monday’s interviews since my team did not know who we were interviewing or what their backgrounds were, we spent time together on Monday researching Tuesday’s stakeholders and drafting questions specific to them based on their background and area of expertise. Going into the second day of interviews, my team and I felt significantly more confident in our ability to make the best use of our limited time with each stakeholder. Our conversations on this day focused largely on the clinical components of our devices. For the intubation box, this meant the cleaning reagents that would be used and whether they would affect the transparency of the box and the types of materials that can be disinfected with UVC versus other methods. For the contactless temperature monitor, feedback from the stakeholders covered input on our color indicator idea, which was taken favorably, an option for the device to not be handheld so as to reduce risk to the person using the device, and cheaper microcontrollers that could possible be found in Malawi. Finally, a key question asked in this day’s interviews is something that is a constant challenge for many global health devices – how can we make the public receptive to the device? We also discovered that a significant challenge in Malawi right now due to COVID-19 is the lack of screening devices or centers, coupled with a lack of proper PPE.

Our final interviews on Wednesday were with Steve Adudans from the Center for Public Health and Development in Kenya, Robert Hauck from GE Healthcare, Dineo Katane-Mkwezalamba from Dzuka Africa, Brian Kamamia from the African Drone and Data Academy in Malawi, and Rhoda Mtegha from Kamuzu Central Hospital in Malawi. While our other interviews were heavily specific-prototype focused, Wednesday’s conversations largely surrounded the bigger picture of designing devices for low resource settings. For example, a key takeaway was that to breakdown the prototypes into their individual components and to determine where every minute part is coming from. This would allow us to analyze how the device is being manufactured and which components could feasibly be locally sourced rather than imported. Additionally, it was reiterated that our devices should be adaptable, affordable, safe, and multi-purpose (if possible). We also discovered that we need to do more research on the rationale behind the current designs when Robert asked us a simple question about the intubation box – Why is it a box? – and we didn’t have an answer.

Our Thursday group workshop consisted of a debrief of our stakeholder interviews and an overview of what we should expect for the remainder of the internship and the internship showcase. Although we began discussing what we learned from our interviews during the workshop, my team felt it necessary to meet again to continue our conversations on Saturday so that we could have more time to debrief with one another and share the feedback that we found most important and critical. After these discussions, my team and I relaxed with a fun fact game that our wonderful TAs had prepared for us.

During this time of laughter, smiling, and goofing around, I realized how much we’ve learned about each other in our four short weeks of purely online interactions, and I absolutely love the close friendships we’ve developed. Majority of the game involved simple questions like “what superpower would you have” or “what’s your favorite snack”, but the final question in the game has become my favorite because our answers clearly show our personalities and who we are, and when it popped up on the screen, we all immediately knew who answered what. Our time together on Saturday was my favorite so far, and I’m excited about where our friendships and work as a team will go (our next virtual meal together is already penciled into the calendar).

This has been the most productive and busiest week of the internship thus far (although I think I may say that every week), and I’m so excited about the work my team has done on our two prototype projects. I am also incredibly grateful for the opportunities we had this week to speak to so many individuals that are experts in their fields and to get to hear the unique insight and perspective they each bring. No other internship out there provides opportunities and activities like these, and I can’t wait to see what’s in store for us these final two weeks.

See you next time,

Lauren