Week Three: June 22, 2015 (haha late again oh dear)

Mikaela Juzswik

It’s a pun in the title, I promise. We’re awesome. Or, at least, Leah’s awesome. Turns out we probably can’t use that as our official team name, but Leah and I are going to keep the two-day old tradition alive. Or perhaps just me. Or perhaps neither of us.

A bit of a recap:

This week, we finally wrapped up calibration with our 3D printers and finished ironing out all the kinks. Our printer seems still seems a bit temperamental, but we have yet to experience a repeat of Friday’s fiasco of the Error 404 variety. Also, we didn’t end up pulling a Harrison, which largely entails:

We’re still not sure how that happened. On the plus side, we think all of the excess filament could be repurposed with Nehuwa and James’s project, which grinds down PLA and ABS fragments and extrudes 3D printer filament! If not, it makes for a lovely contemporary art display.

Things really started kicking up on Tuesday, though, when we got our team assignments. Leah and I reprised our kick-butt team, this time repurposing our talents for creating a mechanical breast pump. Also, around this time, hurricane/tropical storm/tropical depression Bill was supposed to come and drown Houston, so we ended up having a half day off of work for safety reasons before we could figure out anything. We hurriedly shuffled out of work at 11 am on Tuesday, desperately trying to get home before the giant cloud of yellow and red on the weather website came over Rice, threatening to destroy our well-being in a maelstrom of torrential rain—

Turns out the Houston forecasters can’t be right all the time, and we barely had a drizzle. Hurray for safety!

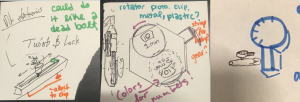

On Wednesday, we returned and began extensive research on our project, the mechanical breast pump. Our goal for the summer is to create a low-cost breast pump for use in Queen Elizabeth’s Hospital in Malawi—it needs to be less than $10, and we also need to be able to make it out of readily-available materials in Malawi. We did a lot of research on current market options for breast pumps, and we’re pretty sure that our final solution will be a mechanical one, as electrical breast pumps are far outside of our cost bracket. As it turns out, most mechanical breast pumps on the market are between $30 and $90 dollars, even before the carrying bags, extra bottles, and other accessories. Furthermore, most of these designs are made with materials that would be difficult to find in Malawi, meaning they probably wouldn’t work for what we had in mind.

We decided to take it back a few steps and look at everything on a very basic level. Leah did a ton of research on breastfeeding and nursing, and we ended up learning a bunch of useful things there: it’s almost universally agreed that breastfeeding leads to healthier babies; it’s better to express milk from both breasts simultaneously rather than just one; there’s an ideal pressure vacuum for highest milk expression for which our design should aim. I started looking at alternative ways to generate suction—basically, a ton of pumps—and started considering low-cost ways to replicate these pumps. A small aquarium pump usually ranges in price from $12 to $20, depending on the size and specs, but both ends of the bracket are already out of our range. Luckily, we aren’t going the electric route, and it still remains to be seen if we can or can’t replicate the mechanism in an electric pump in a more cost-effective manner.

[I’d put in a picture here, but it’s mostly just web searches and scientific journals]

As it stands, we’re still in the brainstorming stage, and I don’t want to bias our opinions by highlighting one idea over another (although, our final idea from Friday, which involved repurposing the pizza boxes from lunch into large fans to generate suction, is definitely a keeper).

Our last activity on Friday was a fun change of pace from the norm: Dr. Ghosn, my project mentor from ENGI 120, came in to give a presentation about project scoping—basically, how to look around the world, recognize a problem, and determine how/if at all to engineer a solution for it. One of the most important things, Dr. Ghosn specifies, is understand what problems the client actually faces: it’s really easy to look on things from an outsider’s point of view and completely miss the point. To emphasize this, he split us into groups and gave us materials that would simulate disabilities—wheelchairs for mobility issues; blindfolds for visibility disabilities; athletic tape for arthrogryposis. Tasks that are normally easy, such as walking up and down stairs, suddenly become incredibly difficult when you’re in a wheelchair and there’s an 8% grade ramp staring you in the face. Operating ID card-swipes is hard when you’re blind and can’t see which of the four possible orientations of your ID is the one that actually has a magnetic strip on it. Even eating breakfast becomes a challenge when you don’t have proper elbow and wrist mobility from arthrogryposis. These tasks are simple when you’re able-bodied, almost forgettably so, but they become challenges that some people simply have to deal with everyday. This, Dr. Ghosn says, is the true key to scoping—getting into someone else’s shoes to figure out the problems that some people face constantly.

The blind (my arm, turquoise jacket) leading the blind (Eckhaire, actually blindfolded).

Next week, we’ll continue brainstorming with the mechanical breast pump and start narrowing down solutions.